Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 2

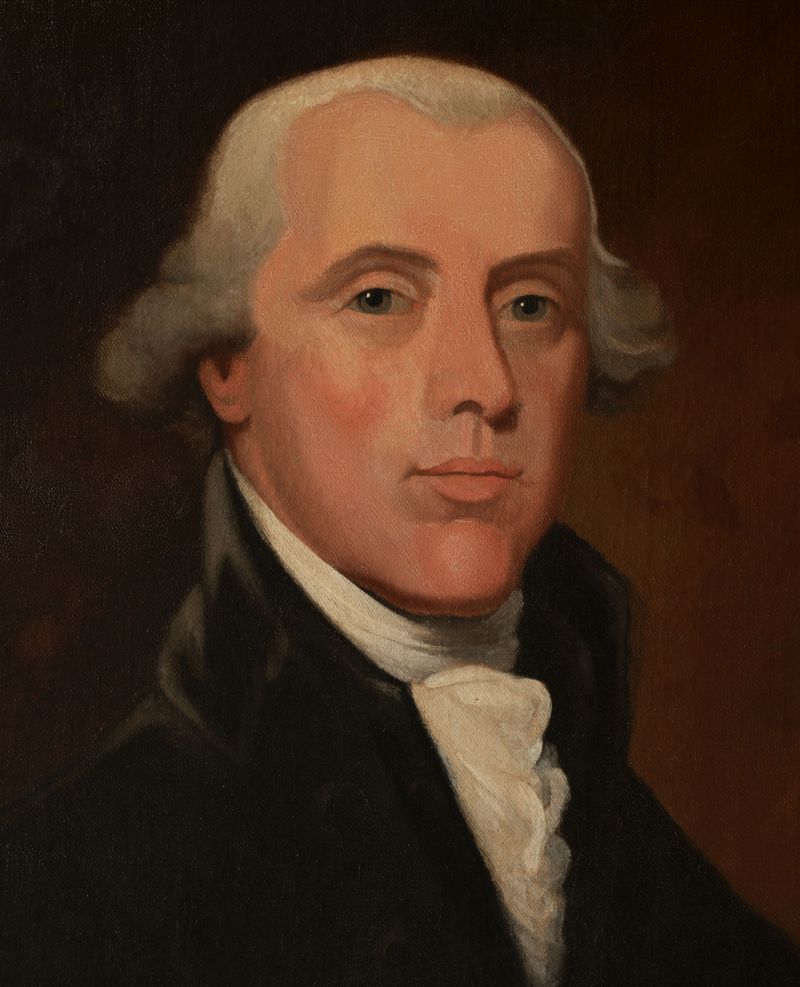

Editor’s Note: Stephen Fried is a journalist and bestselling historian. He adapted the following essay from his recent book on America's first famous physician, Rush: Revolution, Madness, and Benjamin Rush, the Visionary Doctor Who Became a Founding Father (Broadway Books).

Near the end of almost every summer in Philadelphia, people suddenly began worrying about illness, wondering what a cough or an ache might mean. But in August 1793, with the President, his cabinet and Congress returning from summer recess, something more fearsome seemed to be happening.

“A malignant fever has broken out in Water Street,” wrote Benjamin Rush, the leading doctor in the city, to his wife Julia, who was off with their children in New Jersey. The illness had “already carried off twelve persons” on one block — one of whom died only twelve hours after the first symptom appeared. Rush had treated eleven patients so far; three had already died, while the others were barely holding on.

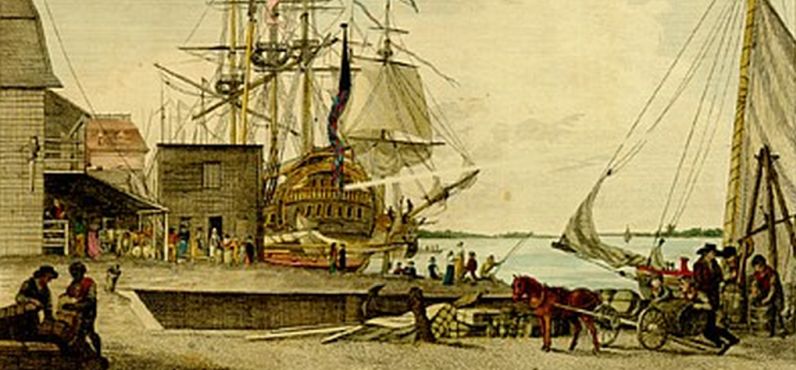

Rush prayed the fever wouldn’t spread “beyond the reach of the putrid exhalation which first produced it.” All the deaths were concentrated in one small area close to the river, north of Market Street, and doctors as well as port officials initially believed that the disease was caused by a toxic air “produced by some damaged coffee which had putrefied on one of the wharves.” At the moment on August 21, nobody was sick except those who lived within a summer breeze of the contaminated coffee.

But then the illness spread, block by block, toward his house. “The fever,” Rush wrote, “has assumed a most alarming appearance. It not only mocks in most instances the power of medicine, but it has spread through several parts of the city remote from the spot where it originated.” He remembered the 1762 yellow fever epidemic from his apprenticeship and had seen a few lesser outbreaks since. He knew the symptoms to watch for in patients, and the sad inevitability that when their eyes turned yellow and their vomit black, there was no hope.

Just that morning Rush witnessed a scene that reminded him of histories he had read of the black plague: a young merchant and his only child died almost simultaneously, the wife frantic and inconsolable with grief. And he had lost nine other patients in different parts of the city.

By