Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Editor's Note: Peter Cozzens is the award-winning author of multiple works of U.S. history, including, most recently, Deadwood: Gold, Guns, and Greed in the American West. His review of Burstein's book was originally written for the Washington Independent Review of Books.

Thomas Jefferson was a complicated man. His towering achievements — author of the Declaration of Independence, first secretary of state, third president, and founder of the University of Virginia — are widely known. He has been both venerated as the intellectual author of the American Revolution and vilified as a slaveholder who carried on a long-term affair with the enslaved half-sister of his late wife. His inner life, however, has eluded biographers, who have variously referred to him as “impenetrable” and “the hardest to sound to the depths of being.”

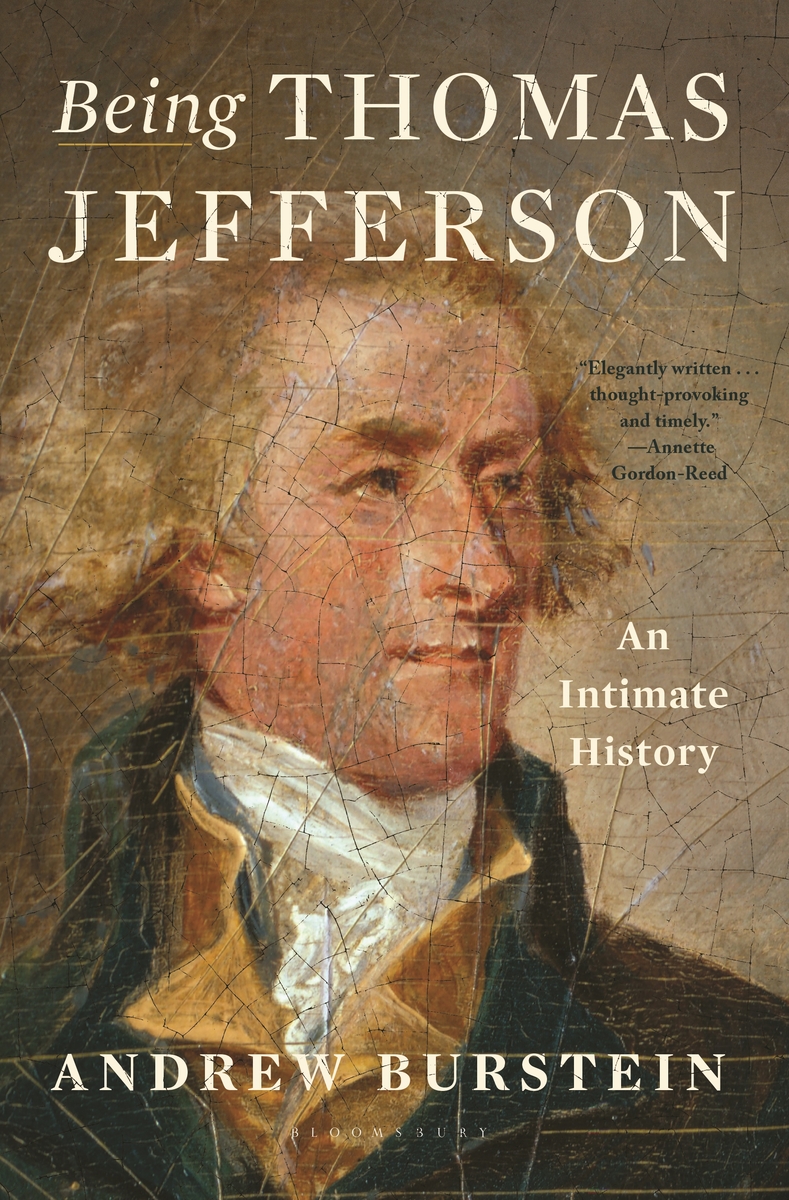

In Being Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History, the distinguished historian of early American politics and culture Andrew Burstein untangles the public from the private man, and in so doing presents a riveting, deeply human study certain to engage the emotions of the reader.

Burstein’s work is balanced; his three decades of study of Jefferson have not blinded him to the Virginian’s shortcomings or to the profound contradictions in his character. Indeed, it is his interpretation of these contradictions that makes Being Thomas Jefferson a uniquely valuable contribution to the literature on our third president. Jefferson emerges as a bookish introvert with an inescapable desire for public office, outwardly restrained but intent on controlling his environment, a consummate rationalizer unable to acknowledge his errors, capable of deep and abiding affection as well as bitter and lasting hatreds. He possessed a burning need to shape his legacy.

Burstein’s penetrating insights are grounded in the historical record, not speculation or “psychobabble.” In Jefferson’s case, the source material is prodigious. He wrote some 18,000 pieces of correspondence and kept a 656-page record of every letter he sent or received. Burstein makes this the framework of the book. Jefferson lived in “an age of typography,” he writes, in which many of the personal letters of eminent men were meant to convey their deepest convictions, which propriety dictated be held in check publicly.

As Burstein explains, “A polished, discriminating style was valued as a manifestation of one’s identity, a way of sharing while adroitly establishing public credentials…Jefferson was famously artful in this manner…[and] extraordinarily adept at communicating emotion on the page.” Nevertheless, “his words require considerable decoding.” It is the author’s ability to convincingly interpret Jefferson’s writings and those of his contemporaries that gives Being Thomas Jefferson its authoritative voice for understanding the inner man, his contradictions, and his motivations.

Burstein also illuminates individuals who had a marked influence on Jefferson but who have been undervalued or passed largely unnoticed. Foremost among these was the Marquis