Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Editor’s Note: Douglas Brinkley, a distinguished professor of history at Rice University and Contributing Editor of American Heritage, has written more than 20 books including American Moonshot: John F. Kennedy and the Great Space Race, in which portions of this essay appear. The book looks at how Kennedy envisioned the space program, his inspiring challenge to the nation, and America’s race to the moon..

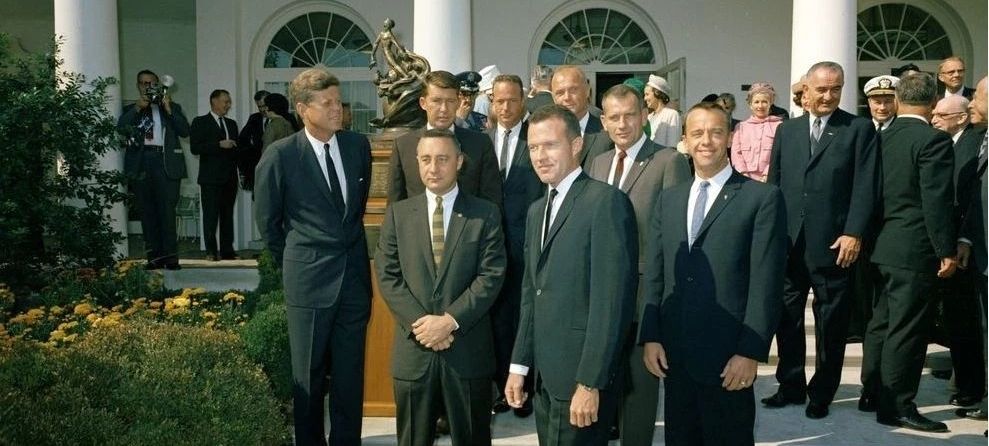

Even the White House ushers were abuzz on the morning of October 10, 1963, because President John F. Kennedy was honoring the Mercury Seven astronauts in a Rose Garden affair.

Kennedy wanted to personally congratulate the “Magnificent Seven” astronauts, all household names, for their intrepid service to the country. His remarks would the end of the Mercury projects after six successful space missions.

At the formal ceremony, Kennedy, in a fun-loving, jaunty mood, full of gregariousness and humor, presented the flyboy legends with the prize. It was the first occasion for all seven spacemen and their wives to be together at the White House since the maiden astronaut, Alan Shepard, accepted a Distinguished Service Award for his Mercury suborbital flight of fifteen minutes to an altitude of 116.5 miles on May 5, 1961. Surrounding Kennedy as he spoke were such aviation history dignitaries as Jimmy Doolittle, Jackie Cochran, and Hugh Dryden.

Instead of recounting the Mercury Seven’s space exploits in rote fashion, Kennedy used the opportunity to drive home his brazen pledge of 1961, that the United States would place an astronaut on the moon by the decades end. Scoffing at critics of Project Apollo (NASA’s moonshot program) as being as thickheaded as those fools who laughed at the Wright brothers in 1903 before the Kitty Hawk flights, he turned visionary. “Some of us may dimly perceive where we are going and may not feel this is of the greatest prestige to us,” Kennedy said. “I am confident that its significance, its uses and benefits will become as obvious as the Sputnik satellite is to us, as the airplane is to us. I hope this award, which in effect closes out the particular phase of the program, will be a stimulus to them and to the other astronauts who will carry our flag to the moon and perhaps someday, beyond.”

For Kennedy, much depended on the United States going to the moon, beating the Soviet Union, being first, winning the Cold War in the name of democracy and freedom, and

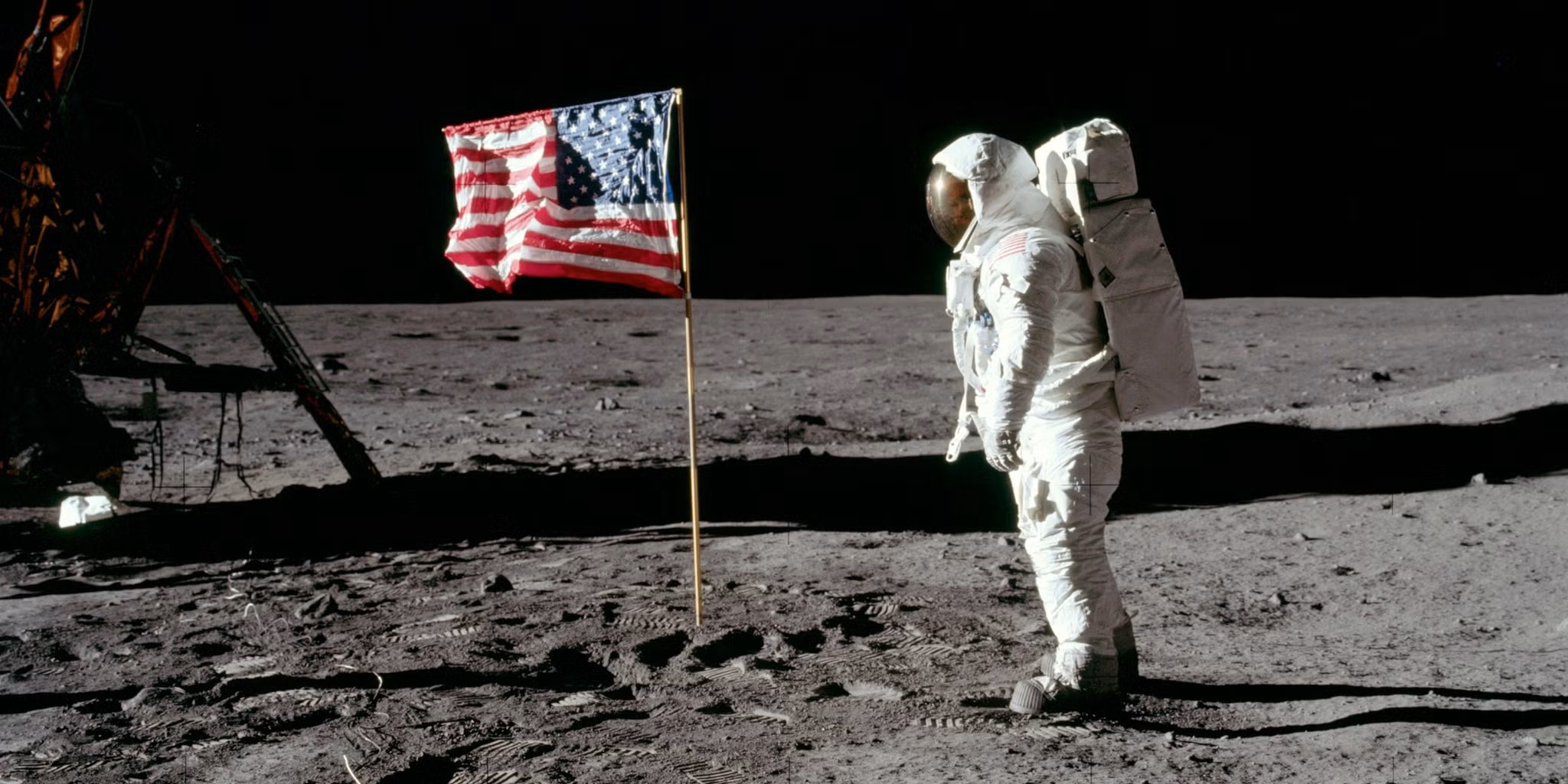

Even though Kennedy wasn’t alive for the fulfillment of his May 25, 1961, pledge to a joint session of Congress to land a “man on the moon” and return him safely to Earth, the marvel of television made it possible for more than a half-billion people to watch the historic Apollo 11 mission in real time, and I was one of them. On July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong gingerly descended from the spider-like lunar module the Eagle with his hefty backpack and bulky space suit, becoming the first human on the moon, I cheered like a banshee. I was only eight years old that summer, and watching all things Apollo 11 – from the nearly two-hundred-hour galactic journey out of the Space Coast of Florida to splashdown in the Pacific Ocean – became my obsession. I didn’t miss a moment of the long, nerve-racking chain of events that led to the Eagle establishing the moon base Sea of Tranquility (named in advance by Armstrong). I vividly remember our astronauts planting the American flag on the lunarscape, bouncing on the desolate moon’s surface, handling instruments, and procuring moon rocks.

My family lived in Perrysburg, Ohio, and we considered Armstrong, from the nearby community of Wapakoneta, essentially a hometown boy. It was stunning that this local kid, who grew up on an Auglaize County farm with no electricity, was leading America into the new world of lunar exploration. When Armstrong said, “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind,” every member of my family was awed at the instantaneous greatness of it all. We were hardly alone in realizing that Apollo 11 had changed all who watched it unfold or lived in its wake. I was proud of my country.

For years I longed to hear Neil Armstrong describe what it was like to contemplate Earth from 238,900 miles away, to explain, in his own words, the thermodynamics affecting motion through the atmosphere both in launching and reentry. Former Johnson Space Center director George Abbey of Houston (now a colleague of mine at Rice University) once told me that many NASA astronauts felt that looking at Earth was akin to a religious experience. Did Armstrong agree? What did it feel like, emotionally, spiritually, to stand on the

Armstrong’s reticence was legendary. He was known to be media shy. But I hoped to persuade him to talk with me about his storied career. Perhaps I could get him to reflect in fresh ways on his lunar experience. In 1993, I wrote him requesting an interview (enclosing signed copies of my books Dean Acheson: The Cold War Years and Driven Patriot: The Life and Times of James Forrestal). I got a polite postcard rejection of the “Not now, but I’ll keep you in mind” variety.

It wasn’t until eight years later that NASA afforded me the privilege of interviewing Neil Armstrong for its official Oral History Project. I was surprised at and honored by the chance to speak in depth with the “First Man” Apollo 11 had changed all who watched it unfold or lived in its wake. I was proud of my country – and thrilled when the date was set for September 19, 2001, in Clear Lake City, Texas. Then, eight days in advance of the big meeting, I saw the horrifying collapse of the World Trade Center towers on TV and listened to accounts of the two other disastrous airplane hijackings. A pervasive sense of gloom and urgency enveloped America.

Like everyone else, I felt shock and repugnance at the ghastly scenes of our nation under attack, feelings that still burn to this day. I was sure my Armstrong interview would be canceled. But it didn’t play out that way. To my utter astonishment, a NASA director telephoned me to say that Armstrong, no matter what, never missed a scheduled appointment. His effort to keep his word was legendary. The post-9/11 skies were largely shut to commercial aircraft, but Armstrong, whose own boyhood hero was flier Charles Lindbergh, refused to cancel his appointment at the Johnson Space Center, piloting his own plane from his adopted hometown of Cincinnati. It was a matter of honor, part of Armstrong’s “onward code.”

The six-hour interview went well. When I asked Armstrong why the American people seemed to be less NASA crazed in the twenty-first century than back during John F. Kennedy’s White House years, he had a thoughtful response. “Oh, I think it’s predominantly the responsibility of the human character,” he said. “We don’t have a very long attention span, and needs and pressures vary from day to day, and we have a difficult time remembering a few months ago, or we have a difficult time looking very far into the future. We’re very ‘now’ oriented. I’m not surprised by that. I think we’ll always be in space, but it

Moments later, I again tried to get Armstrong to loosen up and be more expressive about his lunar accomplishment, to defuse his engineer’s penchant for personal detachment. I had long pictured him in the sultry evenings at Cape Canaveral leading up to the Apollo 11 launch, looking up at the luminous moon and knowing that he and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin would soon be the first humans to visit a place beyond Earth. “As the clock was ticking for takeoff, would you every night or most nights, just go out and quietly look at the moon? I mean, did it become something like ‘My goodness?!”‘ I asked.

“No,” he replied. “I never did that.”

That was the extent of his romantic notions about the lifeless moon. Neil Armstrong was first and foremost a Navy aviator and aerospace engineer, following military orders with his personal best. What became clear to me after interviewing him (and other Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo astronauts of 1960s fame) was that the story of the American lunar landing wasn’t wrapped up in any idealized aspiration to walk on the moon surface; instead, it was all about the old-fashioned patriotic determination to fulfill the pledge made by President Kennedy on the afternoon of May 25, 1961. “I believe,” our thirty-fifth president had said before Congress, “that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before the decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.”

Only one top-tier Cold War politician had the audacity to risk America’s budget and international prestige on such a wild-eyed feat within such a short time frame: in John F. Kennedy, the man and the hour had met. Even Kennedy’s own national security advisor, McGeorge Bundy, thought the whole moonshot gambit scientifically reckless, politically risky, and a “grandstanding play” of the most outlandish kind; and he had the temerity to voice his opinion in no uncertain terms to the president. “You don’t run for President in your forties,” Kennedy snapped back, “unless you have a certain moxie.”

Without Kennedy’s daunting vow to send astronauts to the moon and bring them back alive in the 1960s, Apollo 11 would never have happened in my childhood. The grand idea undoubtedly grew out of a series of what Armstrong called “external factors or forces” – including World War II, Sputnik, the Bay of Pigs, Yuri Gagarin, atomic bombs, intercontinental ballistic missiles, the inventions of the silicon transistor and microchip, and a steady stream of Soviet advances in space. Myriad new technological capabilities unfurled and coalesced with Kennedy’s indomitable “Go, go, go!” leadership style. It’s my contention that if JFK had been wired differently – if he hadn’t had such a

For Kennedy, who himself became a World War II naval hero for his bravery in the PT-109 incident of 1943 in the Pacific Theater, the Project Mercury astronauts were ultimately fearless public servants like him. The NASA astronauts Kennedy had feted in the Collier Trophy ceremony weeks before his assassination volunteered for space travel duty at a pivotal moment in the Cold War. Like Kennedy, these astronauts were courageous, pragmatic, and cool; they were husbands and fathers who, as journalist James Reston noted, “talked of the heavens the way old explorers talked of the unknown sea.”

Kennedy’s New Frontier ethos was based on adventure, curiosity, big technology, cutting-edge science, global prestige, American exceptionalism, and historian Frederick Jackson Turner’s famous “frontier thesis.” All six of NASA’s Mercury missions occurred during Kennedy’s presidency. With Madison Avenue instinct, Kennedy routinely claimed that space was the “New Ocean” or “New Sea.” If so, then he was the navigator-in-chief ordering NASA spacecraft with noble names such as Freedom, Liberty Bell, Friendship, Aurora, Sigma, and Faith into the great star-filled unknown. His talent for converting Cold War frustration over Soviet rocketry success into a no-holds-barred competition for the moon was politically masterful. And the American public loved him for leading the effort.

There were other U.S. politicians who promoted NASA’s manned space program with zeal in the late 1950s and ‘60s, Lyndon Johnson chief among them. But only the magnetic Kennedy knew how to sell the $25 billion moonshot (around $180 billion in today’s dollars) to the general public. Due to Kennedy’s leadership over 4 percent of the federal budget went to NASA in the mid-1960s. In sports terms, he built a team like a great coach, and then played to win. The faith he placed in ex-Nazi rocketeer Wernher von Braun and NASA technocrat James Webb showed that the president was a leader who instinctively knew how to tap the right talent at the right time.

Although Kennedy worried about space budgets, in the end he never shrank from asking Congress for the fiscal increases that NASA’s moonshot required. What makes his leadership even more impressive was the way he wrapped both domestic and foreign policies around his New Frontier moon program in a judicious, cost-effective, and effective way. Building on Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and Harry Truman’s Fair Deal, Kennedy’s New Frontier was activist federal government writ large. What the Interstate Highway System, the Saint Lawrence Seaway, and ICBM development were to Dwight Eisenhower, NASA’s manned space programs were to Kennedy: America, the richest nation, doing big projects well.

It’s fair to argue that NASA’s Projects Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo were just a shiny distraction, that the taxpayers’ revenue should’ve been spent fighting poverty and improving public education. But it’s disingenuous to argue that Kennedy’s moonshot was a waste of money. The

Full of blithe optimism, Kennedy’s pledge set an audacious goal, capping a three-and-a-half-year period in which the Soviet Union twice shocked the world, first by launching the first orbital satellite, on October 4, 1957, and then by sending cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin on the first manned space mission on April 12, 1961, just six weeks before Kennedy’s rally cry to Congress. For a world locked in a Cold War rivalry between the Americans and the Soviets, space quickly became the new arena of battle.

“Both the Soviet Union and the United States believed that technological leadership was the key to demonstrating ideological superiority,” Neil Armstrong explained later. “Each invested enormous resources in evermore spectacular space achievements. Each would enjoy memorable successes. Each would suffer tragic failures. It was a competition unmatched outside the state of war.”

Kennedy, with depth and commitment, articulated a visionary strategy to leapfrog America’s Communist rival and win that high-stakes contest in the name of the capitalistic free-market system as represented by the United States. It was just a matter of figuring out how to do it, using engineering exactitude, military know-how, taxpayer dollars, and political pragmatism.

Kennedy’s moonshot plan was more than just a reaction to Soviet triumphs. Instead, it represented simultaneously a fresh articulation of national priorities, a semi-militarized reassertion of America’s bold spirit and history of technological innovation, and a direct repudiation of what he saw as the tepid attitude of the previous administration. Within months of winning the presidency in November 1960, Kennedy had decided that America’s dillydallying space effort was symbolic of everything that had been wrong with the Eisenhower years.

According to Theodore Sorensen, Kennedy’s speechwriter and closest policy advisor, “the lack of effort, the lack of initiative, the lack of imagination, vitality, and vision” annoyed Kennedy to no end. To JFK, “the more the Russians gained in space during the last few years in the fifties the more he thought it showed up the Eisenhower administration’s lag in this area and damaged the prestige of the United States abroad.”

Only forty-three when he entered the White House, Kennedy represented generational change. When he was born in 1917, West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer was already lord mayor of Cologne, French president Charles de Gaulle was a company commander in the French army, Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev was chairman of a workers’ council in Ukraine, and

At the dawn of the transformative 1960s, these leaders, all born in the nineteenth century, seemed part of the past, while Kennedy and his spacemen were the fresh-faced avatars of a future in which a moon-landing odyssey was a vivid possibility. “I think he became convinced that space was the symbol of the twentieth century,” Kennedy’s science advisor Jerome Wiesner recalled. “He thought it was good for the country. Eisenhower, in his opinion, had underestimated the propaganda windfall space provided to the Soviets.”

Calculating that the American spirit needed a boost after Sputnik, Kennedy decided that beating the Soviets to the moon was the best way to invigorate the nation and notch a win in the Cold War. But he also understood that a vibrant NASA manned space program would involve nearly every field of scientific research and technological innovation. U.S. leadership in space required specialists who could innovate tiny transistors, devise resilient materials, produce antennae that would transmit and receive over vast distances never before imagined, decipher data about Earth’s magnetic field, and analyze the extent of ionization in the upper atmosphere.

President Kennedy bet that a lavish financial investment in space, funded by American taxpayers, would pay off by uniting government, industry, and academia in a grand project to accelerate the pace of technological innovation. He doubled down on Apollo even while calling for tax cuts. Breaking up congressional logjams over NASA appropriations became a regular feature of his presidency. Though the cost of Project Apollo eventually exceeded $25 billion, the intense federal concentration on space exploration also teed up the technology-based economy the United States enjoys today, spurring the development of next-generation computer innovations, virtual reality technology, advanced satellite television, game-changing industrial and medical imaging, kidney dialysis, enhanced meteorological forecasting apparatuses, cordless power tools, bar coding, and other modern marvels.

Shortsighted politicians may have carped about the cost, but in the immediate term, NASA funds went right back into the economy: to manned space research hubs such as Houston, Cambridge, Huntsville, Cape Canaveral, Pasadena, St. Louis, the Mississippi-Louisiana border, and Hampton, Virginia, to the thousands of companies and more than four hundred thousand citizens who contributed to the Apollo effort.

Because NASA worked in tandem with American industry, the agency often received bogus credit for developing popular products like Teflon (developed by DuPont in 1941), Velcro (invented by a Swiss engineer to extract burrs stuck in his dog’s fur on alpine hikes in 1941), and Tang (released in 1957 as a grocery store product). The most pernicious myths were that NASA innovated miniaturized computing circuits and personal computers; it didn’t. NASA, however, did adopt these product innovations for manned-space missions.

Even without the manifest technological and societal benefits of Apollo, Kennedy would have set a course

Identifying the moon as the ultimate Cold War trophy and throwing his weight behind landing there was the most daring thing Kennedy ever did in politics. “Why, some say, the moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? ... We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win.”

For Kennedy, the exploration of space continued the grand tradition that began with Christopher Columbus and flowed through America’s westward expansion, through the invention of the electric light, the telephone, the airplane and automobile and atomic power, all the way to the creation of NASA in 1958 and the launch of the Mercury missions that took the first Americans into space. Kennedy saw the Mercury Seven astronauts he hosted in the Rose Garden as path blazers in an American tradition that extended from Daniel Boone and Meriwether Lewis to Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart.

When he was a boy, Kennedy’s favorite book was the chivalry-drenched King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. As president, he loved when newspapers such as the Los Angeles Examiner and St. Louis Post-Dispatch called his Mercury Seven astronauts “knights of space,” with him as King Arthur. “He made a statement that he found it difficult to understand why some people couldn’t see the importance of space,” von Braun recalled of Kennedy’s visit to the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville in September 1962. “He said he wasn’t a technical man but to him it was so very obvious that space was something that we simply could not neglect. That we just had to be first in space if we want to survive as a nation. And that, at the same time, this was a challenge as great as that confronted by the explorers of the Renaissance.”

What drove Kennedy to gamble so much political capital on his aspirational Project Apollo moonshot? Was it a deep romantic strain (which his wife, Jackie, believed was his true self)? Certainly, he did harbor a quixotic streak when it came to exploration, and an interest in the sea that, he once wrote, began “from my earliest boyhood” sailing the New England coast, observing the stars, and feeling the gravitational push and pull

By the time Kennedy stepped down from the dais at Rice, his memorable words had been seared into the imaginations of every rocket engineer, technician, data analyst, and astronaut at NASA. It was that rare moment when a president outperformed expectations.

“The eyes of the world now look into space,” Kennedy had vowed, “to the moon and to the planets beyond, and we have vowed that we shall not see it governed by a hostile flag of conquest, but by a banner of freedom and peace. We have vowed that we shall not see space filled with weapons of mass destruction, but with instruments of knowledge and understanding. Yet the vows of this Nation can only be fulfilled if we in this Nation are first, and, therefore, we intend to be first. In short, our leadership in science and in industry, our hopes for peace and security, our obligations to ourselves as well as others, all require us to make this effort, to solve these mysteries, to solve them for the good of all men, and to become the world’s leading space-faring nation.”

For Kennedy, spurred onward by Alan Shepard’s successful suborbital arc into space on May 5, 1961, the moonshot was many things: another weapon of the Cold War, the sine qua non of America’s status as a superpower, a high-stakes strategy for technological rebirth, and an epic quest to renew the American frontier spirit, all wrapped up as his legacy to the nation. He would bend his presidential power to support the Apollo program, no matter what.

“I think [the lunar landing] is equal in importance,” von Braun boasted, “to that moment in evolution when aquatic life came crawling up on the land.”

Hundreds of U.S. policy planners and lawmakers followed the leadership directives of President Kennedy and Vice President Johnson. And then thousands of astrophysicists, computer scientists, mechanics, physicians, flight trackers, office clerks, and mechanical engineers followed the White House planners. Millions of Americans joined in the dream, too. Finally, when humans did walk on the moon, five hundred million people around the world took pride in watching the human accomplishment on television or listening on the radio. Even Communist countries swooned over Apollo 11. “We rejoice,” the Soviet newspaper Izvestia editorialized, “at the success of the American astronauts.”

Unfortunately, Kennedy didn’t live to see the Eagle make its lunar landing on that historic day of July 20, 1969. Everybody at NASA knew that Armstrong’s “giant leap for mankind” was done to fulfill Kennedy’s audacious national

Someday the Eagle landing spot and those astronauts’ footprints should be declared a National Historical site. “We needed the first man landing to be a success,” Aldrin later reflected on JFK’s lunar challenge, “to lift America to reaffirm that the American dream was still possible in the midst of turmoil.”

Throughout the United States there is a hunger today for another “moonshot,” some shared national endeavor that will transcend partisan politics. If Kennedy put men on the moon, why can’t we eradicate cancer, or feed the hungry, or wipe out poverty, or halt climate change? The answer is that it takes a rare combination of leadership, luck, timing, and public will to pull off something as sensational as Kennedy’s Apollo moonshot. Today there is no rousing historical context akin to the Cold War to light a fire on a bipartisan public works endeavor. Only if a future U.S. president, working closely with Congress, is able to marshal the federal government, private sector, scientific community, and academia to work in unison on a grand effort can it be done.

NASA has achieved other astounding successes in the realm of space, such as exploring the solar system and cosmos with robotic craft and establishing a space station, but without presidential drive, these didn’t galvanize the national spirit. Kennedy’s moonshot was less about American exceptionalism, in the end, than about the forward march of human progress.

For, as the Apollo 11 plaque left on the moon by Armstrong and Aldrin reads, “WE CAME IN PEACE FOR ALL MANKIND.”