Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Editor’s Note: Michael Auslin is a Distinguished Research Fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution and author of National Treasure: How the Declaration of Independence Made America, which will be published this May by Simon & Schuster.

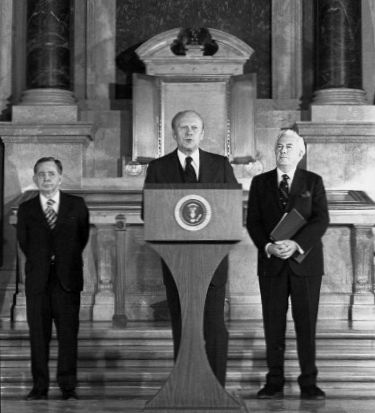

Standing in front of the old, commanding shrine in the Rotunda of the National Archives on July 2, 1976, President Gerald R. Ford summed up the unparalleled importance of the Declaration of Independence. The Watergate scandal, race riots, and the debacle in Vietnam had torn the country apart over the previous decade, but on that day, the president urged his listeners to put those divisions behind them.

The steady, reliable Ford was not known for his eloquence. Yet on the 200th anniversary of the day the Continental Congress had voted for Independence, he gave perhaps the clearest, most succinct appreciation of our founding document. Noting its physical location in the Rotunda “properly central and above all,” Ford called the Declaration “the Polaris of our political order — the fixed star of freedom.” That document, adopted two days after the vote to separate from Great Britain, “is impervious to change because it states moral truths that are eternal,” Ford explained to the world.

As we celebrate the 250th anniversary of American Independence, our founding charter remains central to our national life. The Declaration ties us together, linking us to our past and pushing us forward at the same time.

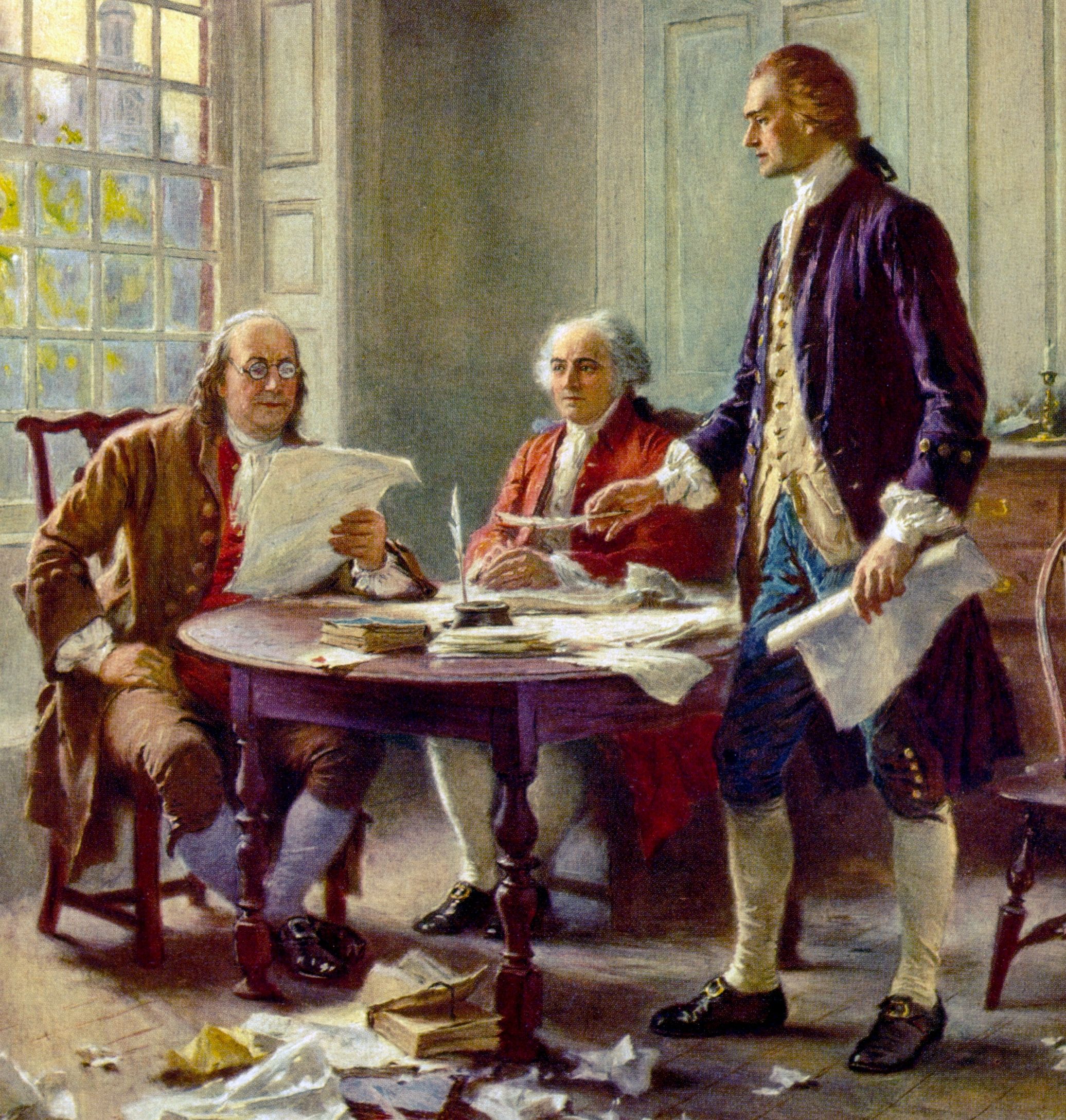

Few would have imagined, on July 4, 1776, that this would be the fate of a statement hastily drafted and haggled over. Once Congress had edited Thomas Jefferson’s draft, cutting out a quarter of his words, including his passionate condemnation of the slave trade, the thirteen colonies adopted the Declaration as sovereign States. No central government held them together.

So important to the States was their individual sovereignty that an “errant a”, which had accidentally been added before “government” in the proof copy of the broadside hurriedly printed up by John Dunlap that night, was quickly removed. The dangerous a in the eighth line, made the sentence read “…whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends [of securing life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness], it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute a new government…” To suggest that the people could institute “a new government” implied the possible creation of a unitary, centralized entity, which in July 1776 was anathema