Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

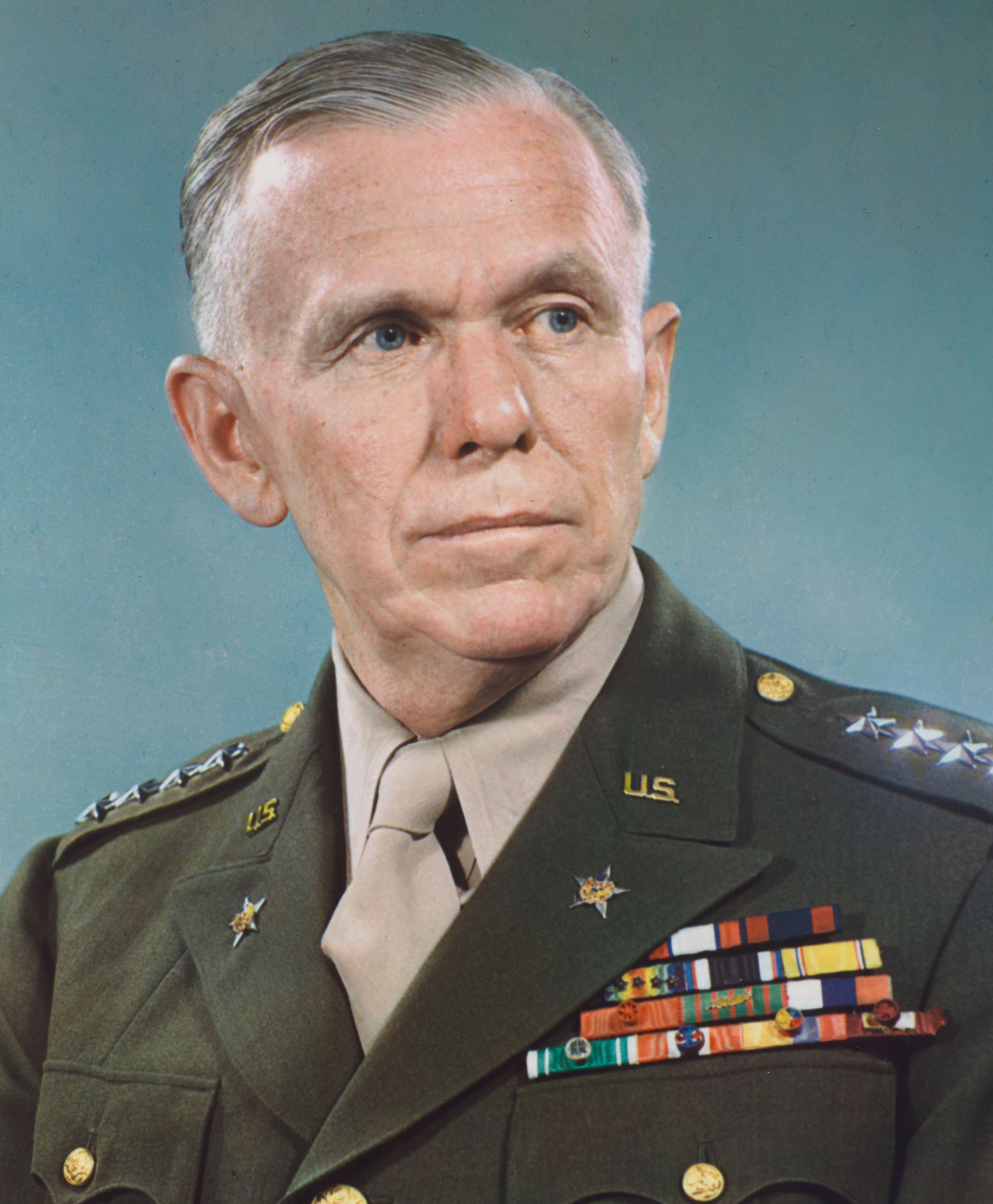

Editor’s Note: General Josiah Bunting III is an educator, military historian, former Army officer, and former superintendent of the Virginia Military Institute. He is the author of several novels and non-fiction books about American history, including a biography of Ulysses S. Grant and The Making of a Leader: The Formative Years of George C. Marshall, in which portions of this essay appeared.

Peter Drucker, theorist and lifelong student of the science and art of management, extolled George Marshall as an exemplar of its most successful practices along with Alfred P. Sloan, president and chairman of the board of General Motors. Marshall was, he felt, an austere prince of the Industrial Age. Like Sloan, Marshall was responsible for the transformation and extraordinary growth of his organization. How he effected that transformation and oversaw that growth, and how the American army fulfilled the purposes for which he was preparing it, constitutes an unexampled testimony to Marshall’s leadership.

But this was management – leadership – of a singular kind. Like Drucker, Winston Churchill praised Marshall’s managerial skills. At war’s end, he called him the Organizer of Victory. He had not led the mighty armies his country sent forth to the battlegrounds of the greatest war in history. He had built them.

It is a heartfelt tribute, very far in spirit from the condescension that tinctured Churchill’s own army chief’s – Field Marshal Alan Brooke’s — appreciation of Marshall’s achievement. Brooke had been quick to point out that Marshall’s experience in war had been limited, remote from battle. As much might have been said of the experience, up to World War II, of Dwight D. Eisenhower, Omar Bradley, and Matthew B. Ridgway. But Churchill had watched as Marshall organized and prepared his army, as he directed the formation of its many and varied components, and as he redesigned its principal maneuver element, the division.

Churchill had also watched as Marshall selected and monitored the work of his nation’s leaders; in fact, he had devised and supported the legislation that enabled him to appoint gifted younger leaders to high positions that the earlier purblind processes of “seniority” would have denied them. Churchill had watched as Marshall integrated the labors of the army with those of sister services and, most important, with those of the