Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2025 | Volume 70, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2025 | Volume 70, Issue 4

Editor's Note: One of the preeminent historians of our time, William Leuchtenburg published his first essay in American Heritage in 1957. We were saddened to hear of his passing earlier this year, but also delighted he published a last book of essays entitled, Patriot Presidents: From George Washington to John Quincy Adams. We thank Oxford University Press for allowing us to adapt one of the essays.

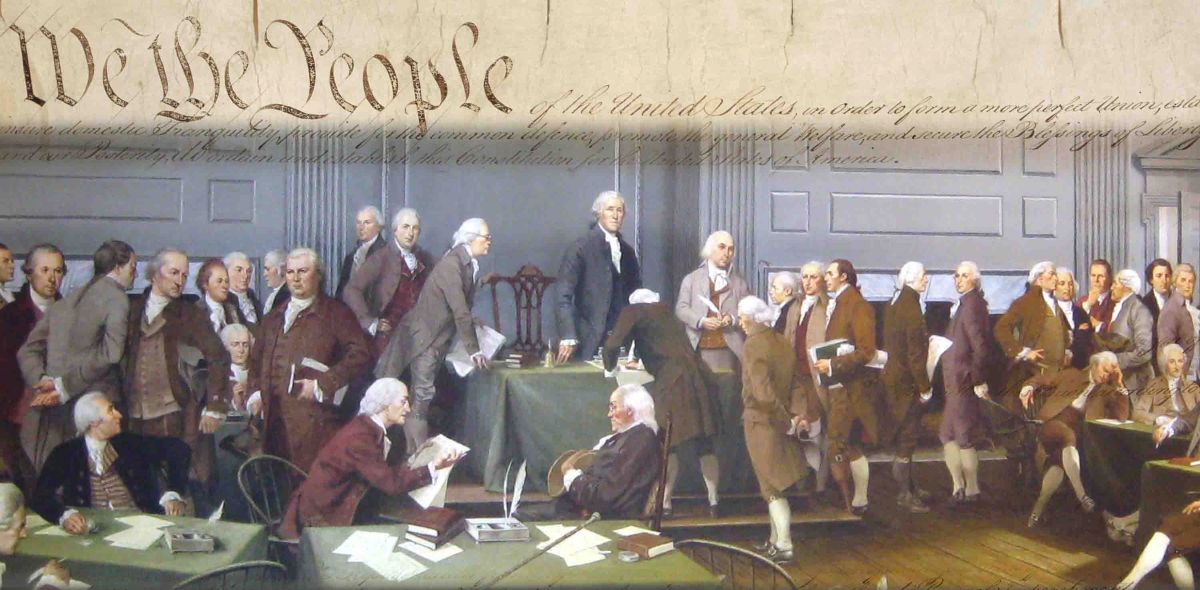

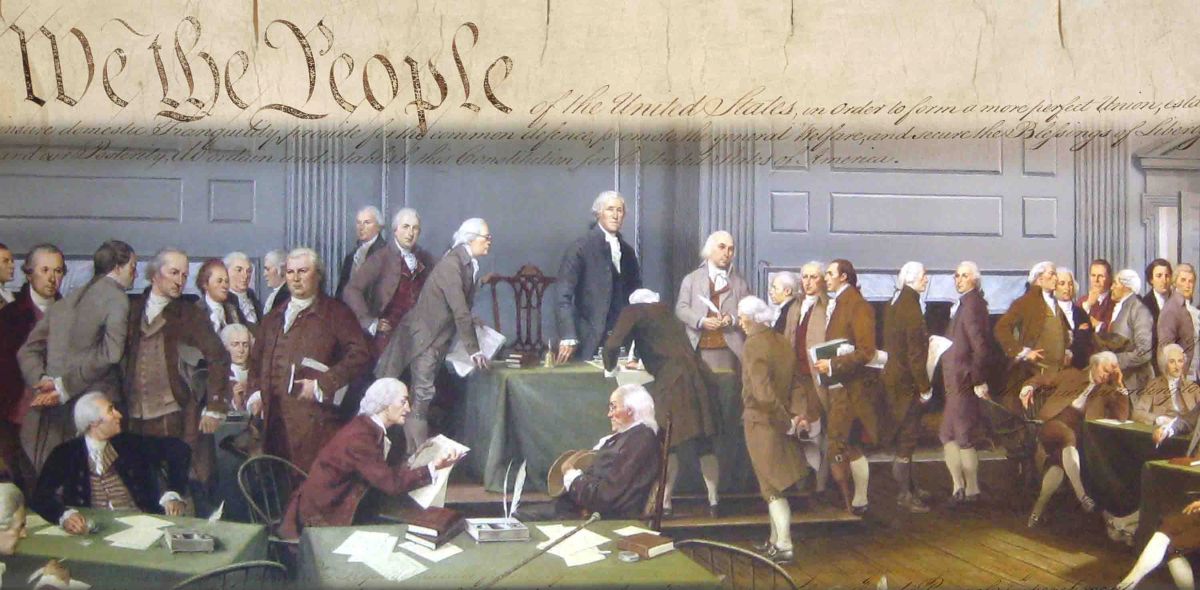

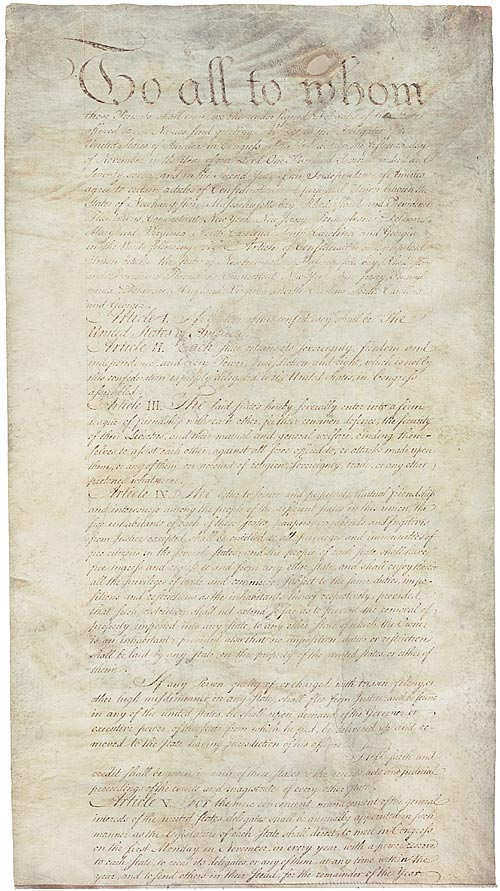

At no time in our history has there been so illustrious a gathering as the corps of delegates who came together in the State House (Independence Hall) in Philadelphia late in the spring of 1787 to frame a constitution for the United States of America. After Thomas Jefferson, the country’s envoy in Paris, ran his eyes over the roster, he wrote his counterpart in London, John Adams, “It really is an assembly of demigods."

Yet, distinguished though they were, the delegates had only the foggiest notion of how an executive branch should be constructed. Not one of them anticipated the institution of the presidency as it emerged at the end of the summer.

One frightful goblin haunted their deliberations. The study of history — ancient to modern — instructed them that republics were always short-lived, and they feared that America might quickly adopt kingship.

“I am told that even respectable characters speak of a monarchical form of Government without horror,” the nation’s foremost patriot, George Washington, reported with a shudder. “From thinking proceeds speaking, then to acting is often a single step. But how irrevocable and tremendous! what a triumph for our enemies to verify their predictions!”

Jefferson shared Washington’s dismay at the prospect. From Paris, commenting on his experience of three years abroad, he wrote the general: “There is scarcely an evil known in these countries which may not be traced to their king as its source, not a good which is not derived from the small fibres of republicanism existing among them. I can further say with safety, there is not a crowned head in Europe whose talents or merits would entitle him to be elected a vestryman by the people of any parish in America.”

Little wonder that during the convention proceedings the delegates heard a young lawyer from Philadelphia, James Campbell, boldly urge in the (approving) presence of Washington. “May every proposition to add kingly power to our Federal system be regarded as treason to the liberties of our country.” Decades of struggle against royal governors had taught Americans