Authors:

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Authors: Stephanie Gorton

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2026 | Volume 71, Issue 1

Editor’s Note: Stephanie Gorton is a prize-winning biographer and journalist. Among her books is Citizen Reporters: S. S. McClure, Ida Tarbell, and the Magazine that Rewrote America, a fascinating history of the team of journalists who made publishing history. Portions of this essay appeared in Gorton’s book.

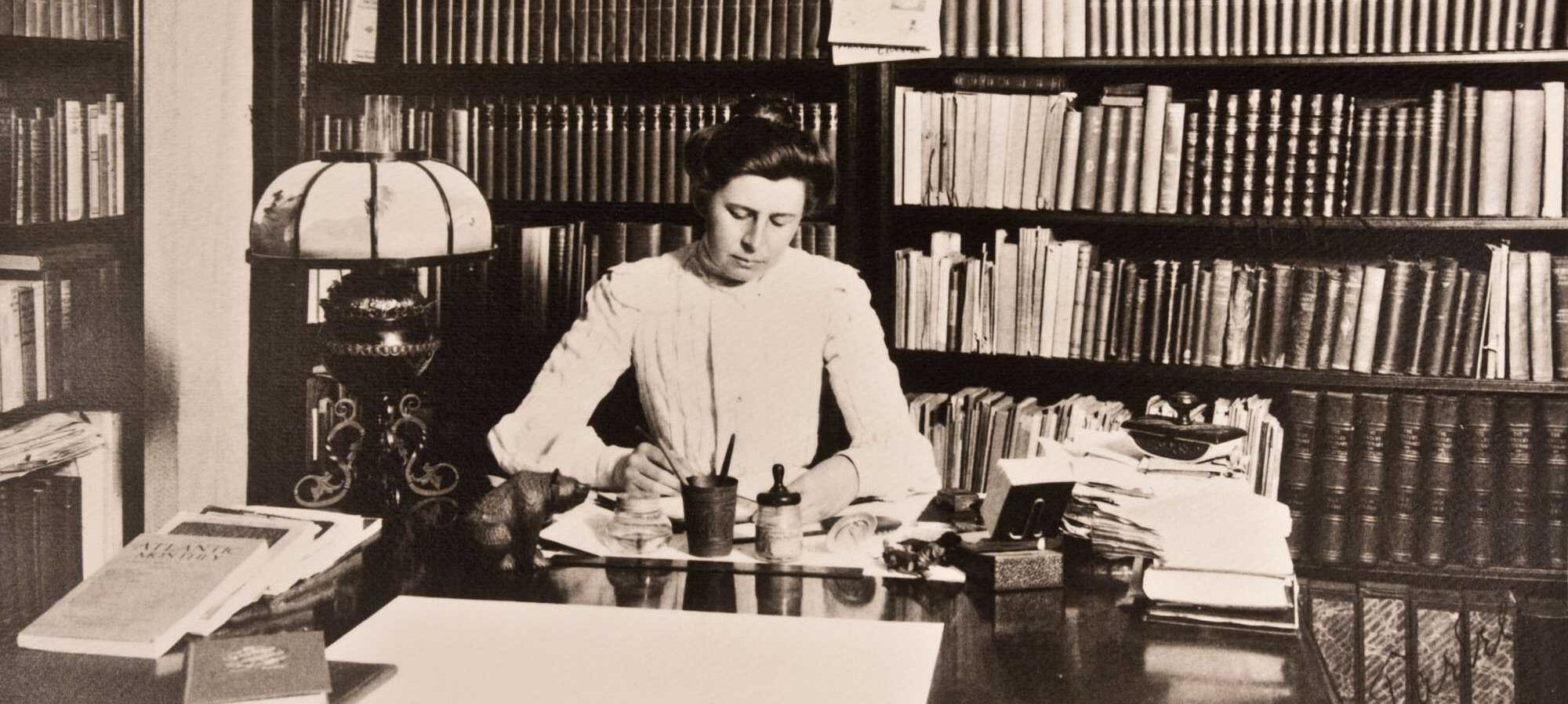

In January 1903, journalist Ida Tarbell felt her usual cheerful stamina wearing thin. In the midst of an investigative series on John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil for McClure’s magazine, she began to long for escape. Not content with monopolizing the oil industry, Standard Oil had swallowed her life, too.

“It has become a great bugbear to me,” she told her assistant, John Siddall, adding that she longed to trade in the task at hand for a trip to Europe. Instead, Tarbell would devote nearly five years to research and write her series on Rockefeller and Standard Oil Company. The landmark exposé ran in McClure's from 1902 to 1904. It was a work “of unequalled importance as a ‘document’ of the day,” observed the Boston Globe. “The results are likely to be far-reaching; she is writing unfinished history.”

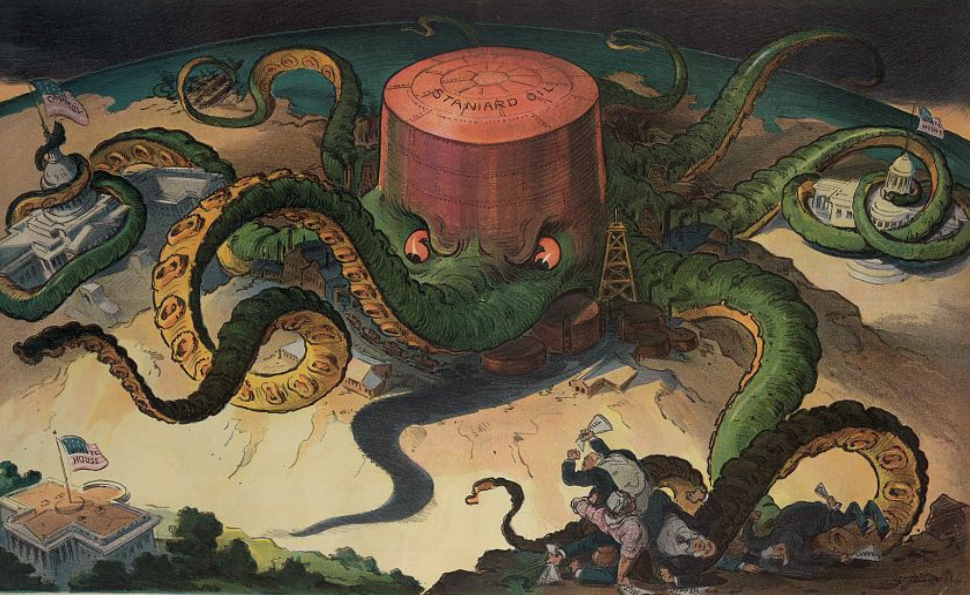

In fact, the series of articles would lead to the breakup of Rockefeller's Standard Oil, widely considered the largest and most dominant corporation in the world at the time. It controlled approximately 90% of U.S. oil production and refining, and 85% of final sales in the nation.

Tarbell’s boss, S. S. McClure, publisher of the magazine that bore his name, told her, “You cannot imagine how we all love & reverence you. You are the real queen of the establishment.” McClure crowed victory to Richard Watson Gilder, editor of rival magazine The Century, that the investigative turn of McClure’s reflected a new social responsibility that now belonged to the magazines. His hope was to “get the people to see that we have been left simply the husks of liberty while the real substance has been stolen from us.”

McClure told Gilder that magazines had a better chance of waking up their readership than any other medium. “It evidently is up to the magazines to arouse this public opinion, for the newspapers have forfeited their opinion by sensationalism and by selling their opinions to a party.”

Throughout the Gilded Age — and its hopeful successor, the Progressive Era — the United States was deeply divided between progressives and conservatives, stretched by recessions at home and wars abroad, and astonished by advances in speedy new communications technologies. Wealth inequality had

All this meant there was a demand for stories that could make sense of the brave new world and no shortage of material for socially conscious writers. A revelatory story or investigation could rock a political administration, bring together a reform campaign, and powerfully articulate tensions simmering in the surrounding culture. In 1892, in the words of reformer and lawyer Clarence Darrow, there was a declared shift in public taste from the romance of “fairies and angels” to instead “flesh and blood.”

The written word never held as much power as during this period of transformations. Actors might have been known by name across the country, and traveling lecturers appeared in towns large and small, but many lacked the means or the time to attend plays and talks. Print was the only mass medium, and “the pulpit, the press, and the novel” influenced an increasingly literate population. In the post–Civil War years, the prevalence of magazines in America mushroomed. In 1860, there were about 575. That number practically doubled every decade until, by 1895, there were more than 5,000. Reporters’ words did not only fill space on the page; they could make or break campaigns, careers, products, and fashions.

Out of all the loud-shouting newspapers and venerable magazines of the day, McClure’s was unprecedented in its determination to entertain, to chase the allure of the new, and to expose injustice. McClure’s stories agitated for change, though they also sought subscribers the way television producers now chase ratings. They exposed the dysfunction of mob-run cities like St. Louis and Pittsburgh and destabilized the monopoly on industry held by oligarchical tycoons, particularly John D. Rockefeller. S. S. McClure’s conviction that a magazine could be a cultural force kept McClure’s sharply attuned to the demands of the reading public. The magazine embodied the muckraking genre; this term for investigative journalism was arguably invented for McClure’s.

By 1900, McClure was widely recognized as one of the most important men in America. In a later reflection in LIFE, the writer noted, “nobody’s hand has been more perceptible than his on the crank that turns the world upside down.” At its peak, McClure’s had more than 400,000 subscribers, soundly beating its rivals Harper’s Monthly, Scribner’s Magazine, The Century, and The Atlantic.

S. S. McClure himself was “a queer bird, but a lovable man and a great one . . . stranger than any fiction,” in the words of one reporter who knew him. He was a perceptive editor and larger-than-Life man, described by his friend Rudyard Kipling as a “cyclone in a frock-coat” and likened to both Theodore Roosevelt and Napoleon. Today he might be seen as part Citizen Kane, part Wizard of Oz: a blazing talent with outsize self-belief and what might today be diagnosed as manic depression or bipolar disorder. He discovered and mentored obscure young journalists—including Ida Tarbell, Ray Stannard Baker, Lincoln Steffens, and

S. S. McClure and Ida Tarbell were born in the same year, 1857. Until their lives converged nearly forty years later, they were a study in contrasts. Sam McClure was a boy out of the Old Country, accustomed to hunger and the scorn dealt to the Irish by his American peers. Ida Tarbell grew up well fed and well read in Pennsylvania’s rapidly industrializing Oil Region, before making a life for herself as a writer in Paris. He was a restless, rumpled figure of a man, a bantamweight five foot six. She stood nearly six feet, a thick topknot of hair giving her extra height and a regal air, and was punctilious about keeping her modest suits brushed and mended. But both were ruled by a drive to prove something to the world — a drive born from coming of age among doubters.

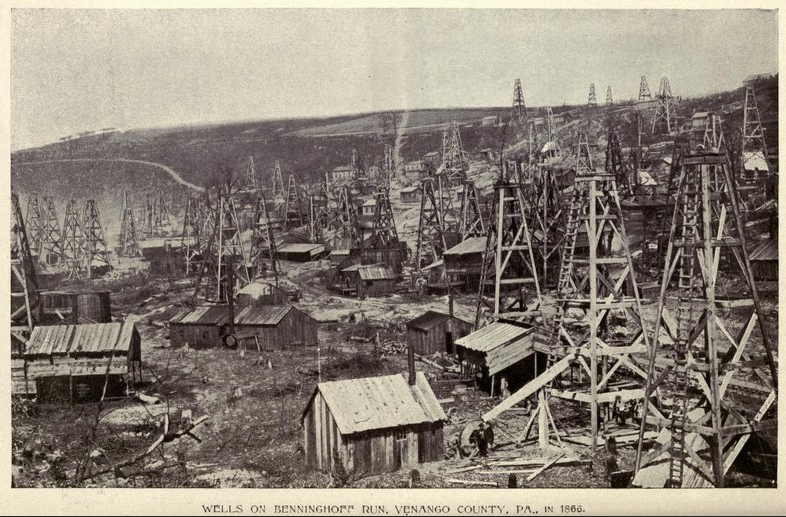

As a child Tarbell grew up surrounded by books, in a landscape glinting from hurried industrialization in Pennsylvania’s Oil Region. Oil seeped through the bedrock of Ida Tarbell’s childhood and returned to occupy her adult years, despite the great lengths she went to to leave it behind. The Oil Region was backdrop to countless dramas of hope, ingenuity, and violent death. Ida later wrote, “Of the pregnant, bizarre, and often tragic development going on about me I remember nothing; yet the uncertainties and dangers of it were part of our daily fare.”

In the year of 1872, a crisis in the community overwhelmed the Tarbells and many of their neighbors. The terror was set off by a scheme called the Southern Improvement Company: a sweetheart deal between John D. Rockefeller and three railroad companies that increased oil freight prices by 100 percent — with an exemption for oil from refineries controlled by Rockefeller’s Standard Oil.

Oil region families rebelled, but even an eventual victory in the courts couldn’t stave off a catastrophic shift for the Tarbells and their neighbors, many of whom went bankrupt before the ruling came into effect. In adulthood, Ida remembered the experience as a bewildering physical trauma, a “blow between the eyes." At fifteen, she could also see that Rockefeller and his ilk, despite the failure of their scheme, were insulated from anything like this fate.

In her resolve to be both educated and self-sufficient, Ida began pushing the bounds of a life of easy convention and social approval. After graduating college and writing and editing for The Chautauquan, a monthly pamphlet that grew from the Chautauqua Assembly Institute’s popular adult education programs, she decided to follow her dream to move to Paris, at the age of thirty-three.

woman, Ida Tarbell through off convention and studied by herself in Paris." data-entity-type="file" data-entity-uuid="fe40d357-348c-4ca6-897e-d9f6a2b767bb" height="336" src="https://www.americanheritage.com/sites/default/files/inline-images/Id%20Tarbell%2C%20LOC.jpg" width="209" loading="lazy">

Ida had disavowed the traditional feminine roles; now she rejected other conventions. “There were friends who said none too politely: ‘Remember you are past thirty. Women don’t make new places for themselves after thirty.’”

One drab day in late summer of 1892, Tarbell opened her door to a jittery man in his mid-thirties who introduced himself as S. S. McClure. He had noticed Ida’s article on the streets of Paris, “The Paving of Paris by Monsieur Alphand,” in the syndicate’s submissions pile back in New York. It was an unexpectedly engrossing article that cast new light on an everyday necessity; the piece revealed the man who held himself responsible for the streets trod by Parisians rich and poor. As he finished it, McClure held it up and said to Phillips, “This girl can write.”

It was the start of a transformative relationship for both. During his visit to her in Paris in 1892, Ida was soon listening to McClure's full Horatio Alger story, from peddling around the midwestern prairies to trying to learn every word in the dictionary at Knox, winning his wife, Hattie, building the syndicate, and a new plan that was sure to take the world by storm. He spoke to her as though she were familiar with Galesburg and New York, and as if she had already met the other people in his life, and knew already that he was at heart a magazine editor; as Ida recalled, it was “always John this, John that, and last a magazine to be—soon.”

After three years in Paris, Ida boarded a steamship headed back across the Atlantic. Her first assignment for the magazine took her to Washington, D.C., where she raced to put together a series on Napoleon. Her next was a twenty-part profile of Abraham Lincoln, which took four years to research and write and which, upon publication, doubled the circulation of the magazine. With each subject, she allowed a surprising capacity for obsession to take over and became immersed in as many archives, interviews, and follow-up fact checks as resources allowed. A woman writer traveling on her own for work—a modern, somewhat bohemian concept—she quickly earned her interviewees’ trust and sympathy, and knew how to shape her discoveries into clear, lively articles.

By the turn of the century, Miss Tarbell wasn’t quite famous enough to be stopped on the street, but she was the most senior writer at a heavyweight magazine that had risen from obscurity largely on her shoulders. McClure’s now had close to 400,000 subscribers, making it one of the most-read magazines in the country. Journalists looked to her technique and persistence as a model; as she told a colleague, “I proceed on the theory that there is nothing about which everything has been done and said.” It helped that she had become McClure’s confidante, worthy of

In 1901, when she was forty-two, Miss Tarbell traveled once again to Europe, this time to visit McClure and pitch the most important story of her career: a series on John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil. It seemed uncertain that this could be the germ of her next great undertaking: Miss Tarbell was used to writing about conquerors and heroes, not the misdeeds of businessmen. She liked writing about the dead, conjuring bold lines of character from archives and interviews. But McClure’s needed a big investigative story on corporate trusts, and fast.

The trusts were already a subject of outrage in the press, yet McClure’s was behind the curve. They needed a subject that already had a direct and personal impact on households across America. In January 1901, news filtered in that an unprecedented “gusher” well had been tapped in Spindletop, Texas. The more the McClure’s staff discussed an oil story, the more it made sense: Standard Oil was the largest and oldest trust of them all, run by an enigmatic tycoon, John D. Rockefeller. By the turn of the century, he controlled more than 80 percent of oil production and sales in America.

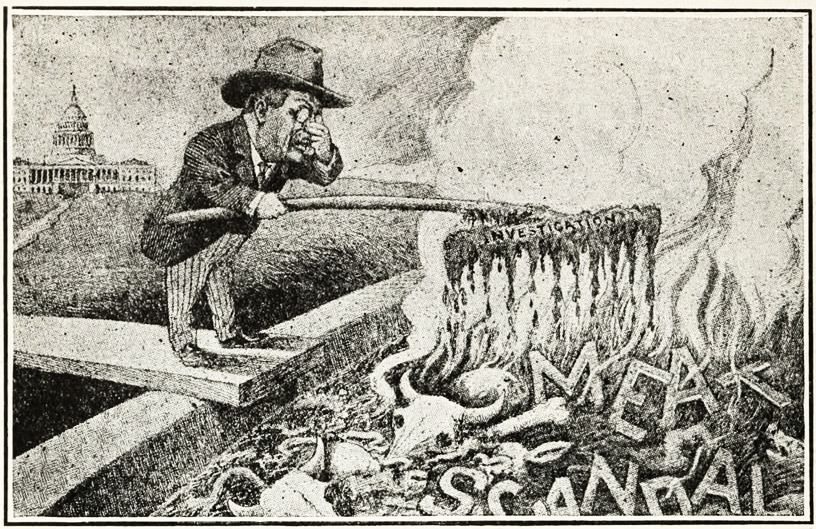

For Miss Tarbell, the topic evoked unwelcome emotions. Her memory of her father’s bankruptcy when she was fifteen was still fresh. Franklin Tarbell regularly talked of Rockefeller and his company as the “Cleveland ogre” and “the great Anaconda.” Newspaper cartoons commonly used snakes or octopi to represent the big trusts, sometimes wearing top hats and always extending tentacles farther than any man could reach. Miss Tarbell tried to write what bankruptcy had truly felt like, before the newspaper cartoons had come about: “a big hand reached out from nobody knew where, to steal their conquest and throttle their future.”

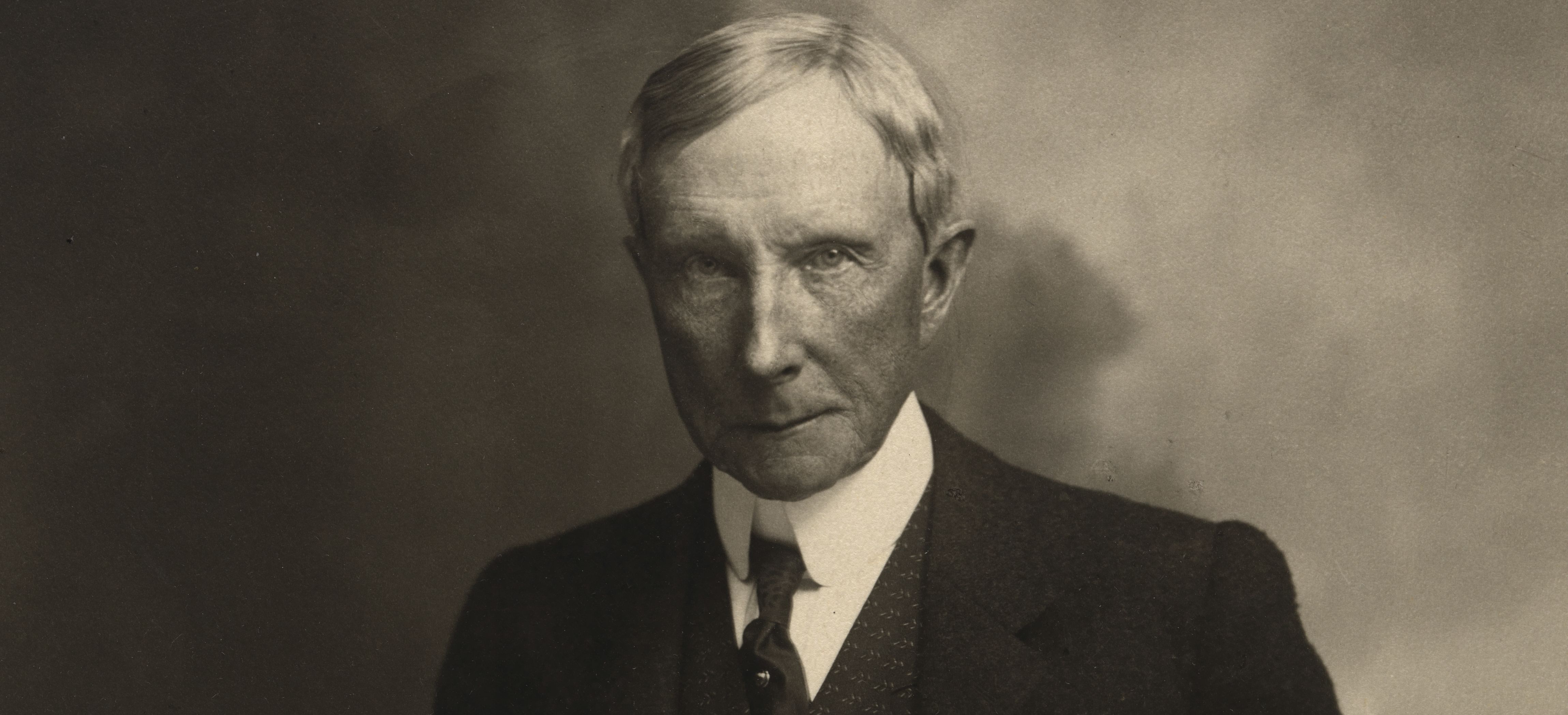

Tarbell described the Oil War from the perspective of the Pennsylvania oilmen; it was in this installment of the series that she pointed at her villain in no uncertain terms: “It was inevitable that under the pressure of their indignation and resentment some person or persons should be fixed upon as responsible, and should be hated accordingly. . . . It was the Standard Oil Company of Cleveland, so the Oil Regions decided, which was at the bottom of the business, and the ‘Mephistopheles of the Cleveland Company,’ as they put it, was John D. Rockefeller.”

The tinge of biblical

Despite high praise in the papers and McClure holding her up as an avenging angel of liberty, one of the final pieces in the series was giving her trouble. She was determined to write a character profile of Rockefeller himself — believing the epigraph she had taken from Emerson’s essay “Self-Reliance,” “An Institution is the lengthened shadow of one man” — but had no access to him.

It took nearly a year to find the right time and place to see him with her own eyes. On Sunday, October 11, 1903, she and two other McClure’s employees slid into the pews at Euclid Avenue Baptist Church in Cleveland, one of the few places where Rockefeller was known to emerge in public from his home in nearby Forest Hills. Tarbell was agitated by the dark, stuffily decorated room, the covertness, and the physical presence of the man she had portrayed as a tyrant. Rockefeller, Tarbell noted, repeatedly glanced at the gallery area where she was sitting, and she wondered whether he knew she was there. Feeling “a little mean,” she gathered her impressions of “the oldest man I had ever seen . . . but what power!”

At the time, Rockefeller was sixty-four and she was forty-six. She saw a man with a large, clear yet deeply lined face, a thin nose “like a thorn,” and “no lips.” She noted his uneasiness, the darting of his eyes, and the sincerity of his voice. His fellow parishioners seemed to admire him, and Tarbell was surprised by the emotion that took hold of her as she took in the scene: “I was sorry for him. . . . Mr. Rockefeller, for all the conscious power written in face and voice and figure, was afraid, I told myself, afraid of his own kind.”

When it came time in the service to shake hands, she went down to join the throng around Rockefeller. He looked Tarbell “fully in the face” before she quickly moved away. A blazing current of revulsion ran through her. “It was too awful,” she recorded just after the fact. In her loose handwritten notes from the morning, she wrote wildly of Rockefeller’s “colorless” eyes and, under them, “the puffiness I have long associated in men and women with sexual irregularity . .

Writing about Rockefeller was an ordeal for reasons that ran deeper than the lines of his features. As a journalist, she was tasked with being a watchdog rather than an activist; the idea of a wholehearted character assassination made her pause. She knew she could not in good faith base her reportage on her feelings alone, but still that antipathy refused to subside.

Tarbell recognized her obligation to impartiality. She saw there was authentic industriousness, skill, and intelligence in the organization Rockefeller had assembled, and titled one of her chapters “The Legitimate Greatness of the Standard Oil Company.” She searched newspaper archives and set Siddall, still in Cleveland, to searching for reports of Rockefeller’s professional deals, charitable gifts, and personal anecdotes; she asked Standard Oil competitors if they would be willing to share any letters or memos they had received from Rockefeller or his men. When it came to reporting on Standard Oil, “I never had an animus against their size and wealth, never objected to their corporate form,” she claimed.

Every word of this statement is worthy of interrogation, for she did have an animus against Rockefeller, a rancor that seemed to gather force as the series drew to a close. She knew there was little intellectual justification for hating a wealthy man for his wealth, even if much of the evidence she had painstakingly gathered bore out her suspicions of Rockefeller as an embodiment of a ruthless fortune hunter. Confirmation bias, or the application of newly discovered evidence to back up an existing frame of mind, undoubtedly figured into her skewering final profile of Rockefeller and his career. Her finished narrative sketched a bloodless tycoon, a parasite bent on bringing financial and moral disaster upon his host.

Even in the early installments of the series, her far-from-neutral feelings about Rockefeller were palpable. As one perceptive historian said of the character who emerged, “a reptilian John D. Rockefeller slither[ed] into view.” Her opinion became the hinge on which the narrative turned, gave it an activist quality, and extended it into a larger argument about society. As she argued, it was the perception and evidence that “they had never played fair” that turned Standard Oil from a company into a cause, a symbol of all that was wrong with big business’s scant regard for the individuals who fed it. “Human experience,” in Tarbell’s words, “long ago taught us that if we allowed a man or a group of men autocratic power . . . they used that power to oppose or defraud the public.” From her initial perception of the Standard as voracious and sly, her framing of the facts smoldered with judgment.

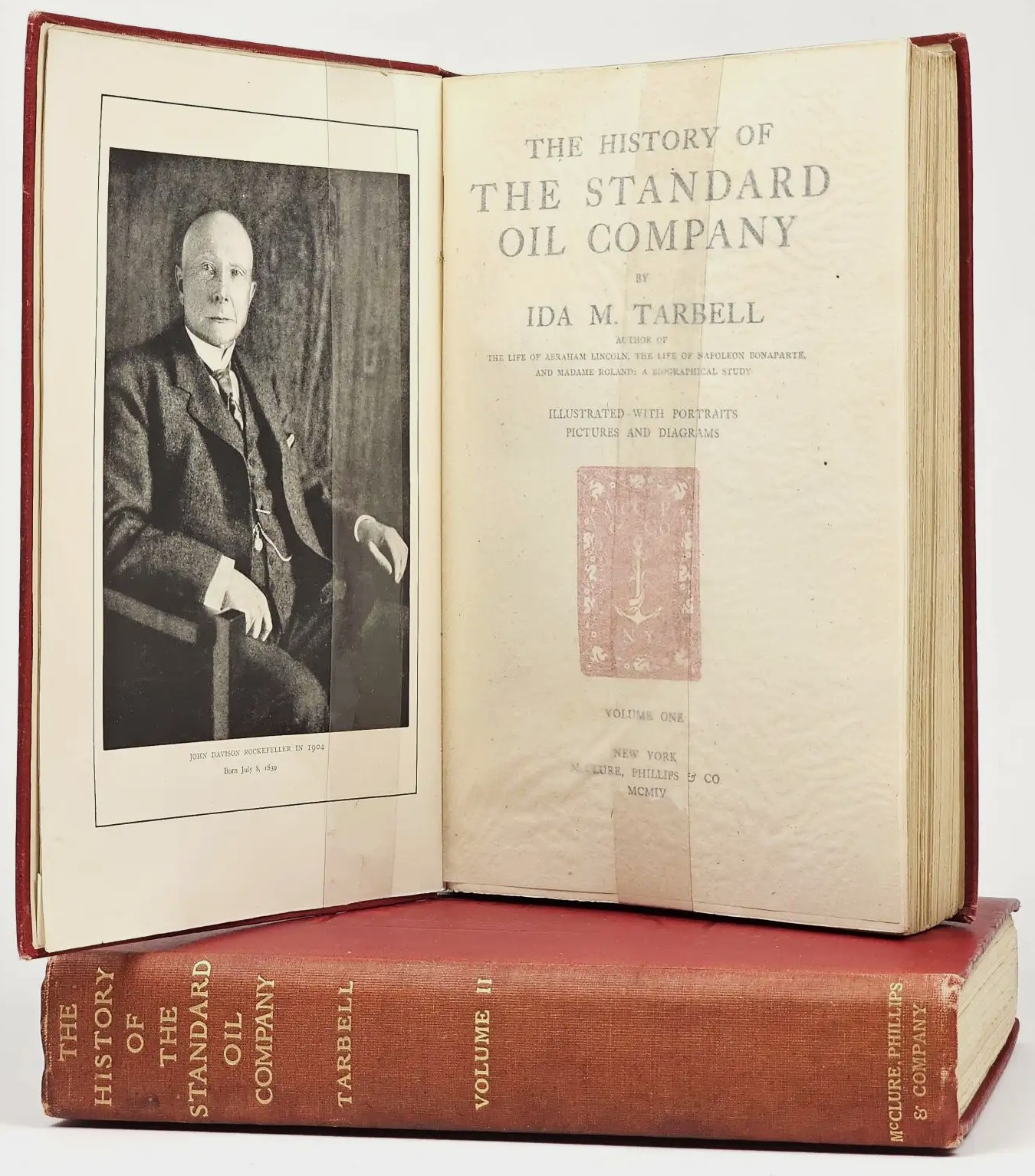

McClure’s gave readers startling photographic portraits of Rockefeller to illustrate Tarbell’s narrative. One was taken after a bout of alopecia— for which, some said, her articles were at least partially to blame—had left him without any hair at all, not even brows or lashes. In another version he wore a black skullcap, provoking a wave of Rockefeller-as-Shylock caricatures. Through 1905, newspaper cartoons showed Rockefeller in a variety of wigs—some shaped like devil horns, others like octopus tentacles, still others like a forest of dollar signs. (A Detroit magazine, The Gateway, demonstrated the injustice of this editorial decision by hiring an artist to doctor a selection of portraits of great Americans—beginning, of course, with Lincoln—removing hair, eyebrows, and beard, to bizarre and uncanny effect.)

Rockefeller, an intensely private man, was no miserly hermit. He has been called “the greatest philanthropist in American history.” Rockefeller put his charity toward causes that Progressives might have applauded, had the source and size of his wealth not gotten in the way. The University of Chicago exists largely thanks to him, and he championed the cause of public health, funding schools at Johns Hopkins and Harvard. He funded a clinic for low-income women, and he also answered a plea from a school for black women in Georgia, becoming a major funder for what would later be Spelman College.

Rockefeller himself was a devoted family man and churchgoer. He and his wife avoided high society in favor of playing with their children and landscaping their property, often rode the elevated train between home and the office, and built a public ice-skating rink next to the family home.

All this beneficence was turned against Rockefeller in McClure’s. Tarbell described his faith as “ignorant superstition.” Of his tightly budgeted household, she noted that “parsimony . . . [was] made a virtue.” She frankly disdained his home in aesthetic terms, putting bad taste on the same moral plane as monopolizing a natural resource. She called Forest Hill, the Rockefeller manse outside Cleveland, “a monument of cheap ugliness.” About his legacy she wrote, “Our national life is on every side distinctly poorer, uglier, meaner for the kind of influence he exercises.”

She concluded that he was a calculating master of compartmentalization; there was a dual personality at work, she wrote, capable of corruption and bullying on a grand scale and clean, simple living in private.

The story of Standard Oil came to represent America’s moral fitness moving into the new century. “What I most feared,” Tarbell later wrote in her memoir, “was that we were raising our standard of living at the expense of our standard of character.” In the mythology of her own family’s struggles, the Standard’s scale had

Much later, as she neared eighty, Tarbell told a friend that Standard Oil had cast a permanent sense of tragedy over her Oil Region home. She wrote, “This district saw and lived through the mad search for petroleum and the long labor to make it fit to give men more light, more power and heat. And along with it went the struggle of a few to get all that was in it for themselves. It was enough to curse the land forever.” Rockefeller was always, for her, the destroyer of home and hope.

After Cleveland, Tarbell returned to New York subdued by her sneaky encounter with Rockefeller, yet driven to finish what she had started. Emotion began to drain from her, and she had some trepidation about her character study being read by an attentive critical audience, as she wrote Siddall in early December 1903: “I think I shall watch the effect this article produces on the press more anxiously than any other. . . . I feel sometimes that my judgment of these papers is all raveled out; by the time I get to the end of one I cease to have any feeling about it at all.”

She underestimated her own ability to convince readers. The Chicago Inter-Ocean called her series “one of the most stirring in our commercial history,” an endeavor that “illustrates most strikingly the strange new conditions of business life in America.” Perhaps most complimentary to her scientist’s heart, the New York World said her work “gives us the same insight into the nature of trusts in general that the medical student gains of cancers from a scientific description of a typical case.” “Woman Does Marvelous Work” exclaimed another paper, while the New York Globe called the series “so thrilling and dramatic that even those superior people whose boast is that they never read a serial made an exception for this one.”

After Tarbell’s write-up from the church, arguments and counter-arguments about Rockefeller’s ethics, and hers, ricocheted through the media, from the Newark News to the Sacramento Bee and abroad, to Canada, Germany, and France. The Nation printed a scornful review, which cut Tarbell deeply. The Denver Republican predicted that Tarbell’s reputation would endure as “the greatest of all literary vivisectionists.” One of the most partisan attacks came from a small newspaper, the Derrick, of Oil City, Pennsylvania, under the headline “Hysterical Woman Versus Historical Fact.” The Derrick was faithful to the Standard, accusing Tarbell

Gender was a frequent theme among critical letters and reviews. In the near-universal acclaim for her Lincoln series, the fact that she was a woman was rarely mentioned as a factor behind any guiding quality of the work. The Rockefeller profile provoked a very different reaction, one that derided a “nagging,” “scolding” Tarbell for seeing her subject through the blurry lens of unchecked subjectivity. In the words of one Detroit-based critic, “it should not be forgotten that Miss Tarbell, as her name implies, is a woman . . . [w]ith all a woman’s weakness of will, ideals of manly beauty, desire for showy entertainment, magnificent dinners, [and] personal adornment.” In sketching a monster, the writer argued, Tarbell had shown herself as being monstrous. She was, like all women, “ruled by her sympathies.”

A diverging but equally reductive tack painted Tarbell as robotic and merciless—unnatural qualities for a woman. One Los Angeles reporter, comparing her to her colleague William Allen White, wrote that while White was bubbling and exuberant, “Miss Tarbell’s wonderful intellect is a pitiles [sic], disinterested, white light. ” She would long be seen as a fascinating enigma; twenty years later, as she toured the Midwest on the speaking circuit and sat by the stage as local luminaries introduced her, she would hear herself described as a “notorious woman” and the subject of long musings as to why she had never married.

When Rockefeller was questioned about Tarbell’s series, he was tight-lipped, saying only that her claims were “without foundation” and that “it has always been the policy of Standard Oil to keep silent under attack and let our acts speak for themselves.” The idea of directly contradicting McClure’s struck him as “unstatesmanlike.” Rockefeller refused to budge from his decision to remain silent. One day, walking near his Forest Hill estate, a friend questioned this policy. Rockefeller told him, gesturing toward a worm in their path, “If I step on that worm I will call attention to it. If I ignore it, it will disappear.”

But to those in his circle, he showed a flinching resentment against Ida Tarbell and her story. Her perspective seemed to fit in with his sense that the world turned against true greatness and leadership.

Despite Rockefeller’s work as a philanthropist, his money was now seen as contaminated. Increasingly, politicians and institutions turned away gifts from the nation’s richest man, whose net worth was around 1.5 percent of the country’s total economic output — roughly equivalent to triple the wealth held by Bill Gates in 2019. Starting in 1904, Theodore Roosevelt declined campaign donations from Standard Oil, keenly aware that public image, once compromised, rarely recovers. A newspaper cartoon showed the harried, top-hatted tycoon asking a newsstand merchant, “Have you any reading matter that isn’t about me?”

Tarbell’s series ran for two years, and would be compiled and released as a book in 1904. She revealed that Rockefeller's Standard Oil monopoly controlled nearly 90% of U.S. oil refining and marketing, utilizing both vertical and horizontal integration. In 1911, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled it an illegal monopoly under the Sherman Antitrust Act, ordering its breakup into 34 companies.

The power of journalism over public opinion surprised and dismayed those who either inherited political leadership or were elected to it. In 1906, in the wake of Tarbell’s series and other reporting in McClure’s on railroad monopolies and lynching, Roosevelt made headlines around the world when he publicly attacked the press, denouncing reporters who threatened his reputation as “muckrakers” and “forces for evil.”

Muckrakers, Roosevelt suggested, were barraging the nation with so much bad news that readers came away with all useful energy, all motivation to improve themselves and the world around them, beaten out of them. "There is filth on the floor, and it must be scraped up with the muck-rake; and there are times and places where this service is the most needed of all the services that can be performed," Roosevelt said. “But the man who never does anything else, who never thinks or speaks or writes, save of his feats with the muck-rake, speedily becomes, not a help to society, not an incitement to do good, but one of the most potent forces for evil."

S. S. McClure, Ida Tarbell, and their colleagues later broke apart, but the craft they invented and the stories they aimed at the troubles of their day have stayed with us. Forbes has described journalists like Tarbell as “the Ralph Naders and Jack Andersons of their time.” Judges convened by New York University’s journalism department listed Ida Tarbell’s The History of the Standard Oil Company in the twentieth century’s top five works of journalism, alongside John Hersey, Rachel Carson, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, and Edward R. Murrow.

Through open-minded collaboration between the various thinkers at McClure’s, the magazine succeeded in creating a whole that was greater than the sum of its parts: it revealed how wealth and power in America worked. Its funding and publishing of revelatory investigations pitted the written word against the growing alliance between politics and business and redefined what ambitious, thoughtful, time- and money-intensive journalism could do.